Real World Data Governance – "Caldicott 2"

In this installment we look at how the value of health information both to the patient and for medical research has been reflected in the recent Health & Social Care Act and discussed in The Review on Information Governance chaired by Dame Fiona Caldicott published in April 2013.

Background – Caldicott 1

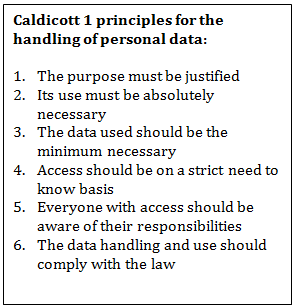

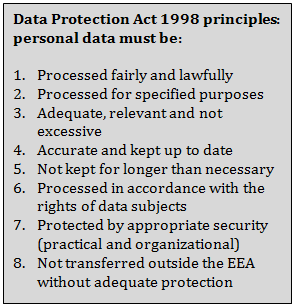

The recent Caldicott review was the second (Caldicott2). The first was in 1997 (“Caldicott1”) and contained 6 recommendations for the protection of personal data. These were published around the same time as the Data Protection Act 1998 and the Human Rights Act 1998. The latter, by Article 8, protects the right to a private and family life, which the state may only interfere with for specific reasons and if necessary and proportionate. A “private and family life” includes respect for private and confidential information. The Data Protection Act 1998 covers the storing and sharing of personal confidential information and gives effect in the UK to the principles in the Human Rights Act 1998.

These principles are part of the legal framework in the UK for the protection of personal data which has at its core the common law duty of confidentiality. To process personal data at all (when the above principles will then apply) in a way that satisfies the common law, one of four legal bases must be met. These are:

- With the consent of the individual concerned (this may be implied or explicit)

- With statutory authority (such as Section 251 NHS Act 2006)

- Through a court order

- When the processing can be shown to be in the public interest

So far as medical research is concerned, patient data that has been de-identified (anonymised) has been used for decades, and following de-identification there are no restrictions on its use. Where the data has been de-identified but there is a code or a key that potentially could re-identify individuals (pseudoanonymised) then data governance arrangements need to be in place to prevent re-identification or ensure it is strictly controlled for compliance with the law. This could be by way of contractual provisions or “assured data stewardship” arrangements. There is a view that any pseudoanonymised data is potentially re-identifiable no matter what the protection arrangements are. The view is fuelled by the developing capability in the UK (and globally) to link different databases containing different types of information together. Linkage of different data sources is enormously valuable for research however.

The sixty years worth of lifetime (“longitudinal”) patient data held within the records of the NHS is of a quality for research purposes that is world leading and the developing linkage capability to other data sources such as those of the Office National Statistics has huge research potential.

Caldicott 2

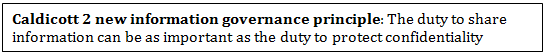

The reform of the NHS enshrined in the Health & Social Care Act by which the power to organize patient care has been devolved to “clinical commissioning groups” of doctors and other healthcare professionals, also addresses the issue of how information can and should be used effectively, including the research potential. Dame Fiona Caldicott was asked to review information governance in the NHS as it currently is, and should be following the implementation of the Act. Following a thorough analysis of how health information is used in day to day healthcare delivery, Caldicott2 endorsed the principles contained in Caldicott1 but also added a seventh principle:

Whilst there is no change to the required legal bases for the legitimate use of personal data, the Health & Social Care Information Centre has, as a result of the Act, a statutory right to obtain personal medical information from patient records when it has been directed to do so by the Secretary of State and NHS Commissioning Board or following a mandatory request from a “principal body” such as the Care Quality Commission, Monitor or the National Institution for Clinical Excellence. NHS England has begun a programme to collect and use healthcare information effectively through “care.data”. The six stated aims of care.data are to:

- support patient choice

- advance customer services

- promote greater transparency

- improve outcomes

- increase accountability

- drive economic growth

The collection involves monthly requests to general practitioners to send in packages of patient data. Currently data relevant to commissioning is being requested, there is a list of sensitive data types that are excluded, and general practitioners are to ensure that individual patients have the right to object to their data being shared, either at all or on any identifiable basis. The governance arrangements required for the collection and use of data in this way are clearly critical for legal compliance and Caldicott2 emphasises this. At the time of publication of Caldicott2 however some governance details had yet to be finalized.

The use by the life sciences industry of the data collected as a result of the new powers enshrined in the Health & Social Care Act will evolve. Research that is protocol driven is however currently and will continue to be enabled by the data provision services offered by the Clinical Practice Research Datalink – developed from the General Practice Research Database that has been offering such services from GPs records for many years.

Privacy enhancement

A new feature that is in development and which has been recognized by Caldicott2 in the context of protecting patients’ privacy is the technological ability to search patient records for clinical trial suitability without the need for identification of individuals. This is referred to as “privacy enhancing technologies” and Cadicott2 comments that these technologies should be used wherever possible to maximize patients’ opportunities to take part in trials but to reduce the burden on GPs to manually identify suitable patients from their practices.

Conclusion

Medical research in the UK has a long and distinguished history and the recent changes to the NHS in the Health & Social Care Act seek to protect and build on this. Most life science companies will be both affected by and be able to benefit from the patient data access capability that will give an increasingly accurate picture of the impact on health outcomes of various treatment regimes. There would seem to be two priorities for life science companies and institutions:

- Welcome the UK’s approach to supporting medical research and the legal framework endorsed by the Health & Social Care Act, whilst being aware of the dangers of a more restrictive approach to privacy existing in places at the EU level (the current passage of the draft EU Data Protection Regulation might potentially result in pseudoanonymised data being treated as identifiable data, with the attendant governance strictures for its use in research)

- Ensure that its own code of practice carefully enshrines the principles in the UK’s legal framework and that it gives the utmost attention to the proper protection of the patient data used in the development of its products.

Real World Evidence Evidence & Data Partnerships

This year real patient data will change healthcare.