The DNA of RWD

Last time we looked at the wider evolving landscape for health informatics and the relevance for the pharmaceutical business model. This article looks at the provenance of real world data (RWD) in the UK and the intrinsic challenges that need to be solved for its full potential to be realised.

Beneath the tidal wave of interest in RWD there are important issues to consider which will help put its use into perspective. A lot is at stake as, in addition to life science applications, RWD is being made available to clinicians, commissioners and the public.

RWD is a spectrum of health data sources that record some series of events. The potential use of these data sets is only beginning to be realised; there is virtually no aspect of healthcare that will be untouched by better analysis and communication of data. In the UK we are fortunate to have a national health system and the academic and commercial curiosity and expertise that place us as one of the leaders in global supply and applications of RWD. To make RWD succeed we need unified strategic objectives, holistic oversight and realistic deadlines or we will extend the timeframe of delivery substantially.

There are tens of thousands of databases that collectively catalogue the status of the population’s health and the care it receives. Some are substantial, such as the Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD), while others may be condition specific, parochial or represent a small group of people. Whatever the dataset, the foundation for usability is the same – records that are as complete, accurate and interoperable as possible. Moreover, if we are to link data sets between domains, for example GP electronic medical records (EMR) to hospital records and increase power by combining global data sets, standards of structure and terminology must be addressed.

In addition to the established medical data sets we must also consider emergent sources of health intelligence such as social networks and search engine term analysis. These patient driven sources are unstructured at the moment but there is no reason why structure could not be introduced to make the analysis more meaningful. An example is the lexicon of healthcare. While we have numerous professional medical terminologies there is no recognised patient lexicon or ontology. This becomes even more important when we consider patient access to EMRs.

So, two key aspects to consider within any given system are completeness and accuracy of the data. Validation of data is an important determinant of the acceptance of such data as having meaningful use. The question we should ask is how do we validate, standardise and improve these data sets? This is best answered by understanding the use of the data both in terms of what we can do now and what we want to do in the future. Areas that yield significant patient benefits should have high priority such as adverse event recording (signal detection), real time surveillance, personalised medicine and biotelemetry. Future uses such genotyping also create the need for record keeping solutions. The return for investing in RWD infrastructure will be improved patient safety, more efficient use healthcare resources and a research environment that is a closed loop. It is also pertinent that these applications will be perceived by the public as validation of the implied contract that patient data is being used for patient benefit, not profit or control.

EMRs are the core of the RWD corpus of data. Collectively they provide the continuous lifetime record of a person’s journey through the healthcare system. On the way we interact with other health services such as social care, vaccination, maternity, disease registers and, ultimately, death. While snapshot information is useful the real power of sustained analysis depends on continuity. This extends to familial connections to understand inherited or environmental effects and patient reported outcomes. A good example is the relationship between primary and secondary care records. These are often seen as independent sources linked by a common patient identifier, but an alternative view that describes secondary care as a series of domains and integrated into the primary record may be safer and more usable for commissioning, analysis and research.

EMRs have been 'in development' in the UK since the early ‘80s. The UK pioneered the electronic capture of patient healthcare (as opposed to payment claims) and now has a legacy of millions of patient records with billions of events. But in today’s environment we must address the issue of the structure and compatibility of these records to meet the purposes industry and the healthcare providers intend.

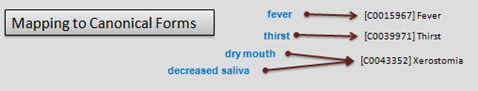

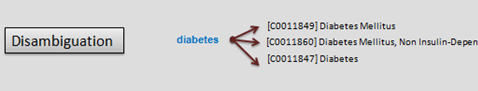

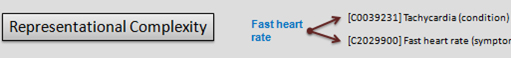

Fundamental to any useful EMR is the ability to capture events and facts in a standardised terminology. This allows compatibility across different systems, whether clinical or research, and renders the records readable by both humans and machines. Coding makes analysis and point of care functionality achievable by introducing methods for handling (click diagrams to enlarge):

Language to canonical forms:

Disambiguation

Representational complexity

In addition to ensuring the accuracy of historical events, coding enables critical functionality. For example using drug codes in a patient records medication history allows suitable software to identify potential interactions and contra-indications. Biomarkers, tests and outcomes provide identifiable end points.

The dominant coding system in the UK is Read codes, developed by James Read and Roger Weeks in the 1980's and continuously evolved since then. Read codes have a hierarchy that reflects how the term being used is categorised. This enables concepts such as signs, symptoms, diagnosis, anatomy, pathology and treatments to be linked. These multiple axes mean that accurate representation is complex. But the codes are essential for clinical support or research analysis.

The Read codes are now integrated as a subset of the Systematised Nomenclature of Medicine (SNOMED) which is a UK and US standard (all new systems used in the NHS must support SNOMED CT). Merging two established terminologies together requires a process of mapping to be undertaken, linking the terms in one to the similar term in another. This is a non-trivial task and the mapping between coding systems needs to be validated if we are to trust the data.

The mechanism of populating EMRs is also an issue given the complexity of the hierarchy and the mechanism by which similar or synonymous terms are presented. We need to incentivise and make it easier for clinicians to enter codes. To improve completeness and accuracy we need to invest in standardised mappings from one terminology to another and improve user interfaces to reduce errors and mitigate poor coding.

We have touched on a couple of core elements of ensuring good health of our health records but the issue goes much wider to include concepts important for drug safety (Meddra) and the future uses of the data e.g. surveillance and biotelemetry.

The usefulness of healthcare information in any application depends on its reliability and whether it is captured in a system with widely understood definitions and meaning. This is true irrespective of use - diagnosis and treatment of patients, analysis in drug development, public health investment or any other. It also requires a systematic, usable and consistent method of capture.

There are numerous staging posts where either the language used or the means of capturing events using that language is less than perfect. These include the ontological framework of medical terms used and understood by healthcare professionals, the system of data capture and the methods of aggregation and analysis. Understanding what these issues are and the impact on the data that results is critical for any company wanting to evaluate and use such information in any aspect of its drug development business.

For pharmaceutical and other life science companies to capitalise fully on the depth of meaning that RWD can lend to drug development it is essential to understand its evolution, the issues that remain to be addressed and what can be usefully relied upon for patient benefit in the meantime.